Excited and eager to start the next leg of this trip, I was up early and said my goodbye’s Wednesday morning. I’d basically be backtracking to where I was. From Bullhead City – 163 west, 95 north to Searchlight, 164 west, I-15 south and finally exit Cima Rd and head north. Whew.

Let’s get this party started.

Cima Road turns into Excelsior Mine Road. A little past the turn off for Kingston Wash, you come into Horse Springs Camp which has a few established camp sites and a primitive restroom.

Continuing on there is Horse Thief Springs. A couple old structures remain that I would have liked to check out in more depth but the close proximity of the locals derailed that plan. The house appears to be something built in the 1920s as you can see more modern materials adorning the roof.

Horse Thief Springs is named for the legendary Chief Colorow Ignacio Ouray Walkara (a.k.a. Wakara or Walker) of the Timpanogo Band of Ute. Walkara was a skilled hunter and horseman from an early age, taught by his father, who was a Ute leader. He also learned to speak several languages, making him a skilled negotiator as well.

In the 1820s, Walkara began accumulating wealth from trading horses and other commodities. He gathered a band of warriors from the Great Basin tribes to raid ranches and stop travelers along the Old Spanish Trail. He became a legendary horse thief, known to many by his yellow face paint.

In the 1840s, he and his band captured hundreds of horses and mules in the Cajon Pass area of southern California. He is said to have traded horses to mountain men such as James Beckwourth and Thomas “Pegleg” Smith for whiskey and other goods. Though Benjamin Davis Wilson, justice of the peace for Riverside County, was sent to track him down, Walkara was never caught. Walkara later developed a trading relationship with Brigham Young in central Utah and negotiated peace after tensions erupted in 1853. – Source Credit BLM

There’s still some active mining taking place on Excelsior Mine Road. There are a few detours that you have to take but they are marked by signs and present no problems. At the summit of pass there were small patches of snow, as well at snow packed up on the peaks.

Dropping into California Valley you can see the Nopah Range and into Tecopa. The white patch of ground that the road appears to be leading to is the next stop at the Tule Spring. There’s a few structures standing here but couldn’t get a single shred of information on what happened here.

Next stop was supposed to be checking out all the Tecopa Mines but research just prior to my trip revealed they have just been purchased and are now all private property. While nothing was fenced off or any signs posted, I respected the fact and moved on.

I’m fortunate in the fact that I have got to explore here a few times, spending a good amount of time in the War Eagle and Noon Day mines. Both being the largest workings I have ever set foot in and that’s only covering the main haulage tunnels. By the sounds of it, the new owner seems open to hosting events/access to outsiders and hopefully it’ll go the ways of something like Cerro Gordo.

At approximately the same time that Pablo Flores discovered Cerro Gordo, silver -lead ores were discovered at Tecopa, named for a local Paiute who befriended early settlers and located south – southeast of Death Valley at the southern edge of the Nopah Range some 10 miles east of the park boundary. ” Known as the Gunsight Mine, it is related to Turner’s discovery in name only, because his discovery is presumed to be much farther north northwest in the Argus Range.

Little is known about the early history of this mine except that it operated from 1865 to 1882 and that a ten -stamp mill and three furnaces were constructed in 1880. Prior to that time, ore from Tecopa had been smelted and processed at Resting Springs and Ivanpah. By 1881 some 40 men were involved in the mining operations. A 1,000- foot tunnel was dug to open a vein composed of galena at the surface that changed in depth to a carbonate ranging in value from $ 60 to $ 400 a ton, with an $80 average.

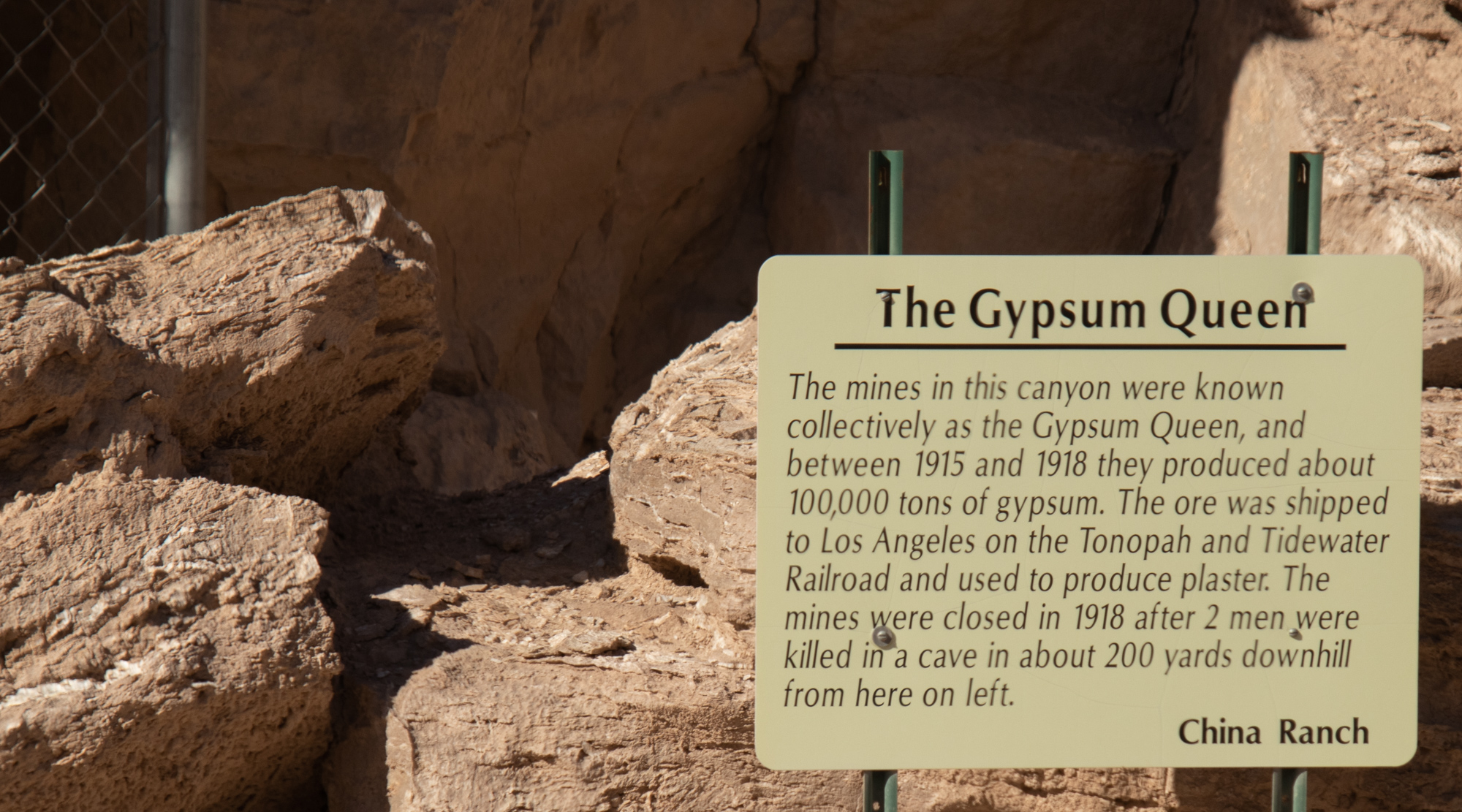

Due in part to the interest generated by the Greenwater mining rush to the northwest of the Gunsight Mine during the early 1900s, the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad pushed its

railroad construction northward through the Amargosa Valley in an attempt to obtain the developing copper camp’s business. Completed to Tecopa at the time of Greenwater’s

collapse, the railroad provided the Noonday and Gunsight mines, both owned by the Tecopa Consolidated Mining Company, with an outlet for their silver ores. The company quickly shipped a 30 – car train of ore worth $ 40 per ton . By 1910 an 11 -mile standard Noonday mines to Tecopa station , where high – grade values were shipped over the Tonopah and Tidewater to smelters at Murray, Utah.Between 1912 and 1928, the Tecopa Consolidated Mining Company produced $ 3,000,000 in silver and lead, becoming California’s leading silver – lead producer between 1917 and 1920.

By the time declining lead prices and ore values forced the Tecopa to shut down in 1928,

148,000 tons of ore averaging nearly $24 a ton were produced, two-thirds of which was lead while the rest was silver with a trace of gold. By that date the Tecopa mines’

production had reached nearly $ 4,000,000, making them the biggest metal producers in the Death Valley and Amargosa country.After World War II the mines, which had been inactive during the Depression, were purchased by the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. The mines were operated with a crew of some 45 men until March 1953, when operations closed .

Couple pictures from my last time there in 2014.

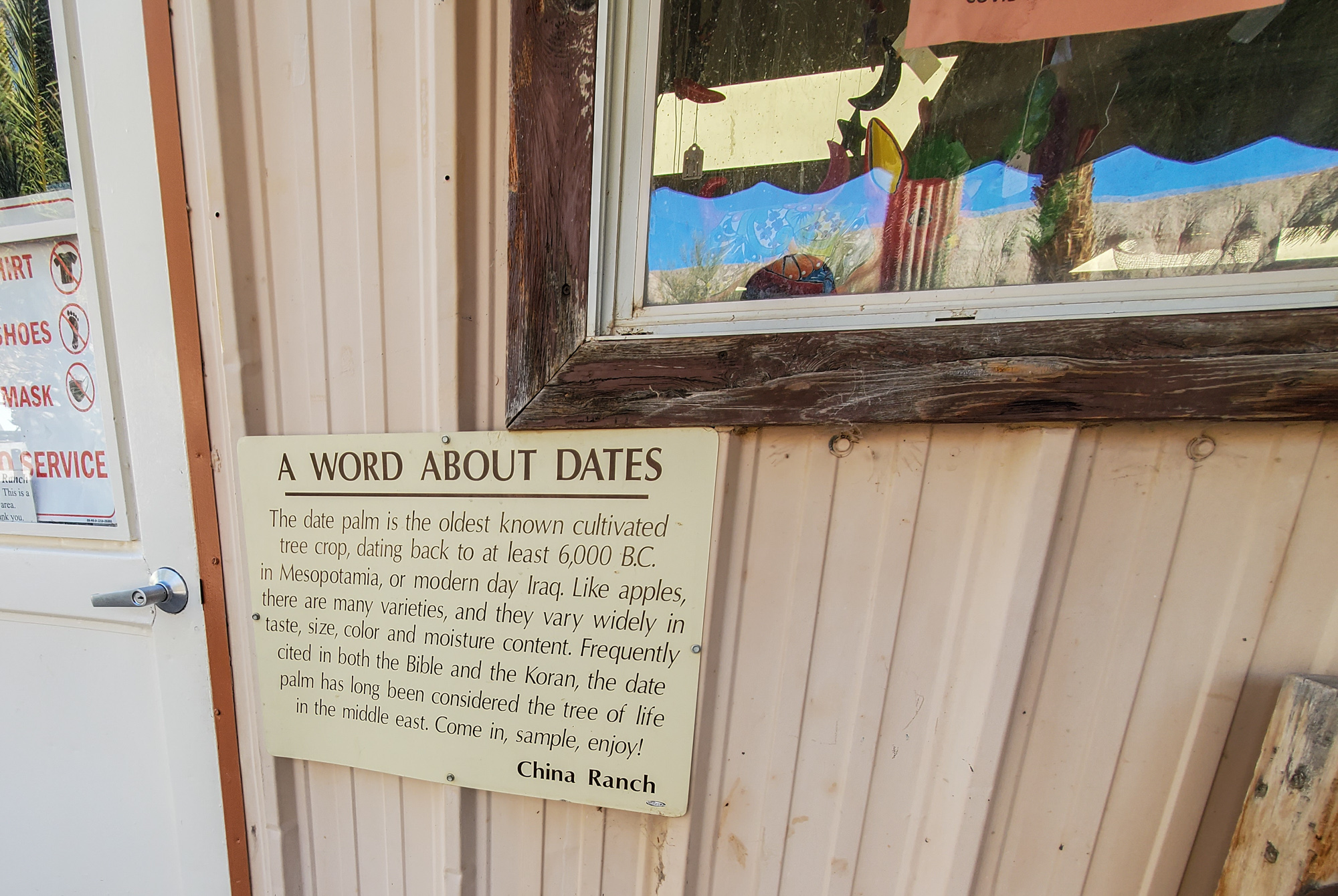

Headed towards the small little “town” of Tecopa, then turned to the south on China Ranch Rd to check out the date farm and pick up a shake.

In the 1890’s a Chinese man named Ah Foo came to this canyon from the Borax Works in Death Valley. He developed a successful ranch, raising livestock, hay, fruits and vegetables to help feed the local silver miners and their draft animals. The “China Man’s Ranch” became a favorite resting spot, with it’s cool running stream and beautiful trees.

In 1900 Ah Foo disappears somewhat mysteriously though the name has stuck. After many changes of owners and financially unsuccessful ranching attempts over the next 90 years, the current owners began planting young date palms in 1990, and opened China Ranch to the public in 1996. – Source Credit China Ranch

Such a solid date shake. I didn’t want it to end. Super cool place to check out and wish I would have stopped to check out the small museum they had. From the parking lot there’s some hiking trails that head south along the Amargosa River.

Had to back track a bit towards the Tecopa Mines where I’d pick up at the Noon Day camp, making my way towards the Amargosa River.

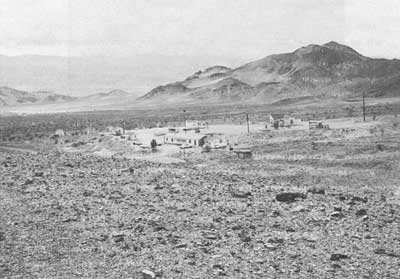

Located due east of present day Tecopa on the San Bernardino/Inyo county line lie the remains of a mining community that went by several names – Brownsville, Mill City, Tecopa, Noonday City, Upper and Lower Noonday Camp. Established by the Finley Company in the 1940’s to support the nearby War Eagle, Noonday and Columbia lead mines.

The site was taken over by the Anaconda Copper Company, who constructed the lead ore concentration mill during 1947-1948. The mill’s large water tank marks the location. Near the now rapidly deteriorating mill and debris pool is the site of Lower Noonday also known as “Married Mans Camp”. 18 to 20 foundations can be found buried in the brush, along with a small graveyard, the slag from the 1870’s smelter and a few adobes. Across the Western Talc road and up the arroyo is a cliffside dugout dwelling. A water pipe ran from the well to Upper Noonday. Along Furnace Creek Road is Upper Noonday Camp, or “Single Mans Camp”.

Used by Anaconda’s employees from 1949 until 1957, and then Western Talc’s employees until 1972. It was abandoned, scavenged by the locals, and torn down in 1978 which makes this a relatively young ghost town. Foundations of the supervisors and guest houses, several slabs that supported the kitchen, boarding house, and bunkhouses are evident, along with a lot of debris. Prominent is the cinder block vault that held the script currency the miners could use at the company commissary.

Roads from this site go to the Noonday and War Eagle mines, worth the exploration. A bit farther back on the Western Talc road is the talc mine, a large white open pit. The remains of the mining operation can be found, collapsed timber structures, foundations, slabs, rock walls, and equipment mounting pads.

Lead mining ended in 1957 when the U.S. Govt reached it’s strategic stockpile goal, the Tecopa and Darwin lead mines – which worked three shifts during the war years – closed. Talc went out of favor due to it’s asbestos content. Visible from Highway 127 and the Old Spanish Trail are the landmark Tecopa bins, built in 1944. One was for lead, the other talc. The lead ore was trucked to the UP siding at Dunn and shipped to smelters in Utah. – Source Credit ghosttowns.com

The area beyond this sign was used historically as a settling basin for liquids used in silver and leak milling operations. The soil contains unsafe levels of several heavy metals and other substances that could pose a health hazard. Please stay out of this basin for your own safety and that of others.

Past the Western Talc Mine you reach the trail head for the Amargosa River. For the most part it’s rocky, rough and finding the right line is key. When I went through, I’d highly recommend high clearance and 4wd as there’s some rocky spots that need to be navigated.

The Amargosa River has often been called the crown jewel of the Mojave Desert. Its origins begin in the southern Great Basin desert in Nevada. The river meanders 200 miles, largely underground but surfacing to form life-giving oases near the communities of Shoshone, Tecopa, and through the Amargosa Canyon. It finally winds its way to ancient Lake Manly on the floor of Death Valley at 282 feet below sea level, the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere.

Because of geographic isolation caused by climate change, the river’s oases are the final aquatic refuges for many rare and endangered species that have survived here and speciated over the past 10,000 years. Species include the Amargosa vole, Amargosa Toad, the Amargosa pupfish, speckled dace, Amargosa niterwort, and 250 bird species, including the least Bell’s vireo and southwestern willow flycatcher. Overall there are approximately fifty unique species found only along the Amargosa. – Source Credit calwild.org

Once you drop into the canyon you get your first glimpse of the Amargosa. There was a considerable amount of water flowing above the surface, always a neat sighting when you’re in the desert. As the trail heads south towards Dumont Dunes, sightings of the river are numerous as well as crossings.

It’s also at this point that you get to see the first signs of the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad roadbed.

The Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad was constructed through the Amargosa Desert from 1905 to 1907. The railroad was built mainly to haul borax from Francis Marion Smith’s Pacific Coast Borax Company mines located just east of Death Valley, but it also hauled lead, clay, feldspar, passengers and general goods across the desert. Francis Marion Smith was one of California’s most successful entrepreneurs and mining tycoons. In 1890, he incorporated the Pacific Coast Borax Company and operated the largest borax mine in the world at Borate, located 11 north of Daggett, California, with the Borate and Daggett Railroad running a more than adequate service between the two stops. Smith was also responsible for building several interurban and rapid transport systems around Oakland, California and San Francisco, California.

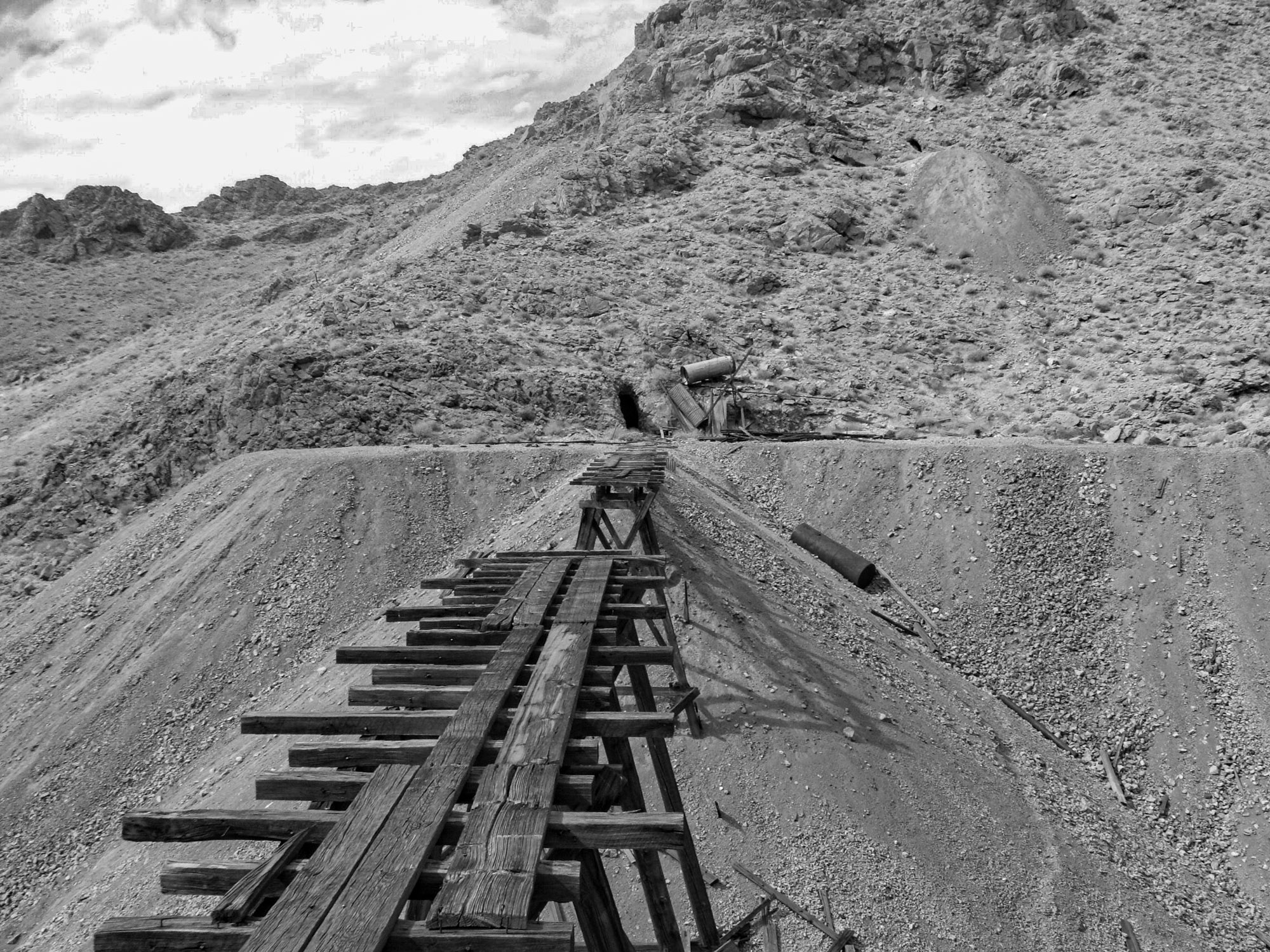

Much of the roadbed was built up with tailings from the borax mill in Death Valley, which gave the grade a white appearance as it snaked its way up the Amargosa River. Trestles as long as 500 feed and deep cuts were necessary to enter the canyon. Tent camps were erected in the wide wash to house and feed the railroad construction gang. Heat drove many of the workers away, some would spray others with water as they worked in the stifling head. They would then switch to take a turn at the pick and shovel. Lack of materials, a dwindling workforce, and temperatures reportedly reaching as high as 140 degrees forced the abandonment of further construction during the summer of 1906. Construction of the railroad had been estimated at $3 million. However, the Amargosa River section pushed the project way over budget. Later calculations show that the construction of the railroad up the Amargosa River cost more than $40,000 per mile.

The first train service between Ludlow and Sperry ran in February 1907. The railroad was originally intended to run from Tonopah, Nevada to San Diego, California (the “tidewater”), but never made it to either on its own rails. It was famous for being the last of the three railroads built to cross the Death Valley region, and outlasting them by over 30 years providing dedicated and reliable service to the desert residents. The T&T also formed part of a potential north-south transcontinental railroad route, connected together by four different US railway companies, later used as the basis to potentially form a Mid-Pacific Railroad.

The railroad operated from 1907 until 1940, when it suspended operations due to a lack of profitable traffic. The rails were taken up in 1943 for use in World War II and the company itself was officially abandoned by 1946. – Source Credit Back Country Adventures – Southern California

Native inhabitants of this region used foot trails to travel between water sources like the Amargosa River. In the late 1700s, Spanish traders traveled these same routes between New Mexico and Los Angeles. These historic routes are collectively called the Old Spanish Trail. Antonio Armijo and Kit Carson likely passed through this very wash in 1830 and 1848, respectively. After this route was established, many explorers, settlers, and soldiers used it on westward journeys. In the early 1900s, the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad was laid along this very same corridor. It was used to haul ore out of these hills. You can still see portions of the railroad grade along Sperry Wash.

From here I got back on the 127 and headed north a bit before I exited to the west. This would take me into the very southern portion of Death Valley. The plan from here was to check out the Ibex Spring, then the Moorehouse Mine that’s situated behind it.

Throughout the active operations of the Moorehouse, the Monarch and the Pleasanton from the 1930s to the 1950s, and the intermittent mining of the 1960s, Ibex Springs was exploited as a water source for mining and living needs, and a fairly substantial camp appeared. Since the talc mines have remained in private hands until recent years, the remains of this camp have escaped large-scale destruction, and dominate the present scene.

The talc mining camp at its height consisted of a dozen wooden buildings, including a bathhouse with plumbing, several sheds and storehouses, and several living quarters. Most of the buildings were constructed of boards and plasterboard, and had electric lights and propane appliances. The spring was improved by the talc miners by means of a concrete spring house and collecting tank, from which water was pumped or flowed to the shacks. – Source Credit nps.gov

The road leading back towards the Moorehouse Mine was washed out and it would have been a longer hike then I wanted to do at that point in the day. It was getting late and I still needed to log some miles and get to camp. Looking back I’m bummed I didn’t suck it up and do it though… I’ll be back.

From Ibex Spring, drove back to Saratoga Spring Rd and continued south.

The camp spot I had mapped out turned out to be absolutely perfect. The view was vast and ever changing with the clouds rolling through. There was also a well used and established fire ring ready to go. Cooked some food, drank some cold snacks and hit the bed a bit after dark thirty.

The Rainbow Talc Mine lays within the Ibex Dunes. Interesting read about it and all the legalities surrounding mining within National Parks. LA Times – Dust-Up Over Talc

To be continued!!!

Excellent story and pictures, my wife and I have done all of this. Like you said the Tacopa Mines were bought and we met the owner 10/23. No signs saying keep out we headed off road towards one of the distant mine shafts and a four runner we had passed on the highway began to follow us, I told my wife it was just someone like ourselves doing some exploring but as it turns out it was Ross the new owner, he was pleasant and offered us a tour, we didn’t go as we had what turns out to be a long lonely road to CIMA and I-15 but it was just as you said and loaded with mines all along the way.